Ce qu'on voit et ce qu'on ne voit pas

The title of this charming pamphlet, better known in English as What Is Seen And What Is Not Seen (July 1850, by Claude-Frédéric Bastiat) poses a question so much more basic than the purportedly simple economic question it asks about a broken window, i.e; why do performing artists so readily fall into the trap of only seeing and accepting the simplest understanding when viewing a printed text, as opposed to at least peeking behind the curtain?

1. Starglow

My prejudices against the usefulness, validity and meaning of time signatures (TSs) are reasonably well known. Sadly, if one speaks about the meaning, function and usefulness (or lack thereof) of TSs (and therefore of barlines), the deep-seated, virtually religious convictions that one so frequently and quickly encounters, make any such discussion an exercise of pissing into the wind. Therefore, in order to better approach some understanding of the notional and notational problems we face “laying out” any written text, I shall stray to a different, closely related field, i.e. a very late poem by Louis Zukofsky (full disclosure, my father) which context (at least for musicians) may not be so fraught with shibboleths.

I grew up with the notion that music could be considered, or indeed was, the highest form of speech. This did not mean the usual flatulence of music as a universal language conveying great emotions etc. Rather, it meant that the components of speech – the stresses, the syntax, the emphasis, what Bunting referred to as “thump”1, i.e. the speech patterns, the sibilants, glottals, et al – all appeared in music in some highly refined form; and in the final analysis, the desire and need to understand, endow, appreciate and convey meaning when reading (or performing) a text (whether poetry or prose, read out loud or silently) was/is directly comparable to the problem of determining musical structure and phrasing, and to the activities of performing music.

In pursuit of this thought, let us make the assumption that the choices a poet makes about how a poem is “laid out” may in some sense be comparable to those made by a composer in determining how to lay out a musical metric structure. To explain this further, allow me to dissect a somewhat arbitrarily chosen poem from LZ’s last series of poems 80 Flowers.2

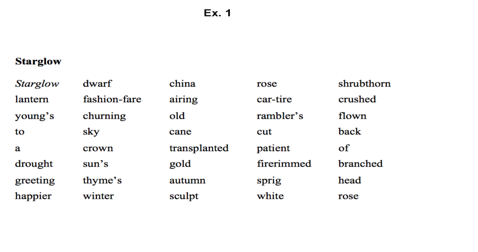

The original reads:

Starglow

Starglow dwarf china rose shrubthorn

lantern fashion-fare airing car-tire crushed

young’s churning old rambler’s flown

to sky cane cut back

a crown transplanted patient of

drought sun’s gold firerimmed branched

greeting thyme’s autumn sprig head

happier winter sculpt white rose

Notice that the poem takes up eight lines, with five words per line. This is not that different from a piece of music with eight phrases of five bars each, or perhaps eight bars of ![]() .

.

QUESTION: does emphasizing the "fiveness" of each line help us achieve some clarity and understanding of the meaning?

The following presents the poem "laid out" on the page in a grid with each word receiving equal spatial weight.

This presentation does little to aid understanding, or help convey meaning. Furthermore, the result of reading it in a fairly equal-time-per-word style (and yes, I have heard it done in that manner – I hasten to add, not by my father) is extraordinarily clunky and boring.3

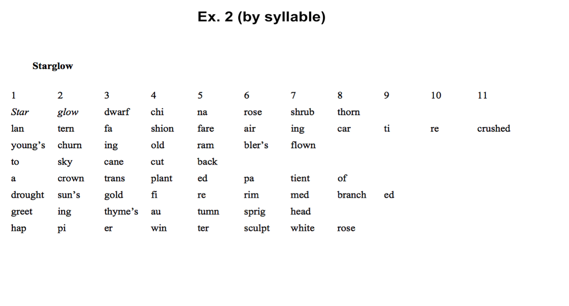

Perhaps we should not think five words per line. Perhaps we should consider the syllable count, which differs from line to line. Such a version might be presented as follows:

While this version does have the possible advantage of showing that each line has a different syllable count, and may therefore be more revealing of internal structure than the previous example, but in terms of meaning, the syllabic version (Ex.2) is even less helpful than (Ex. 1), and a reading giving each syllable equal weight, duration or meaning is so stilted that it can hardly be described as English.

What, then, to do with this recalcitrant lump?

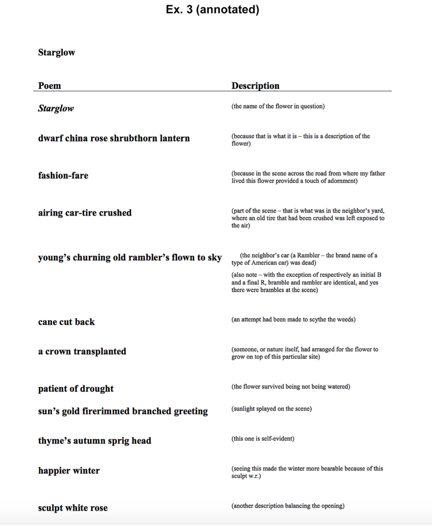

Perhaps it might be best read or understood as:

This last version does have the advantage of telling one where to make some syntactical breaks, and therefore has more "air" in it, and "breathes" better. That makes the meaning somewhat clearer, even without the explanations I have appended.4

Very well, you may say, if (Ex.3) is what the man wanted, or might have been prepared to accept as an interpretation, or might have preferred as a reading, why did he not just write it utilizing a different number of words per line? LZ is obviously prepared to accept a different number of syllables per line, something classical prosody supposedly disallows, so why the self-imposed formal restriction (for that is what it is) of five words per each and every line.5

Two answers immediately come to mind. The first involves plasticity; the second historical acknowledgment and analogy.

In regard to plasticity, we quickly discover that (Ex.3) is not the panacea we might have hoped for. It is simply too fixed. It allows few, perhaps no, possibilities. Put another way, (Ex.3) eliminates far too many of the interconnections and ambiguities in the original poem.

As an example, consider the word "crushed", which occurs at the end of the original second line.

Most probably "crushed" refers to the tire, but it might also refer to the car (the "rambler" of the next line). (Ex. 3) minimizes that ambiguity. (Ex. 3) forces us to read the poem in a certain way, and does not provide the reader-performer flexibility to make their own decision(s) regarding cross-references, or trajectory of phrase. One of the great blessings derived from using a fixed form such as the original version is: "everyone" recognizes it to be a convention; a neutral mechanism. Ergo, such a fixed form allows for, or even provides, maximum (syntactical) freedom and flexibility; enjambment6 is expected, probably even de rigeur.7 Plasticity is maximized.

A second answer to the question as to WHY the poem was not written in some form of (Ex. 3) reflects the importance of historical acknowledgment.

My father was obsessed with previous formal poetic structure (and with word counts per line). In English poetry, one of the most famous of these poetic structures was the pentameter, usually the iambic pentameter.8

While my father had little interest in what passes for a traditional pentameter, his method of laying-out poems in lines of five words each was his homage to that classical meter, and the five-words-per-line form simultaneously allowed him to achieve three objectives:

(a) to acknowledge, revivify and transmute the old form;

(b) to irrevocably associate himself with the tradition of the great English Lyricists;

(c) to create – out of the old – an astonishingly flexible NEW form, which looked both to the past and to the future, thereby perhaps putting him in a category with a Wyatt, or perhaps a Malherbe.9

And now, you may well ask - what does any of this have to do with the writing or reading, understanding or performance of music?

To my mind, EVERYTHING.

Plasticity, historical context and perspective are perhaps the essence of composers' fundamental concerns.

As regards plasticity, the comparable question (for music) is:

Do you wish to notate in a fashion that at least appears to be highly specific, or rather, is it preferable to provide a neutral background, which you hope the performer will recognize as such, and will feel free to ignore, or at least look beyond?

In regards historical context and perspective:

To what extent are music notational choices forced upon you, depending upon when you are writing; for whom you are writing; as well as what are you referencing or looking back upon?

Remember that:

ALL NOTATION IS A COMPROMISE.

No choice of meter solves every contingency.

While most meter changes are an indication of certain aspects of the composer's thought process, sticking with a single meter does not necessarily signify abjuration on the part of the composer regarding alternative metric stress. Nor is the use of constantly changing meters the most efficacious overall answer, given that clarity in one aspect may very well muddy the waters elsewhere. Finally, whichever style is chosen, be it one meter, or many, the choice is almost definitely not dispositive, as the decision to change, or not to change TSs, may have been quite arbitrary, or perhaps not even well considered. In short, no matter the choice, it is still incumbent upon us to look beneath the surface of the notation.

There is, however, a new wrinkle to the ancient "UNANSWERED" question. Before -- when a composer wrote in only one uniform meter throughout a movement, one could assume maximal variety, just as in the LZ poem discussed above. Now -- when a composer (purportedly) chooses a specific set of meter changes, what are we to make of those changes? Are our choices of stress, accent and shape etc., completely restricted because of the changing meters, or are they not?

As examples:

Babbitt told me many times (in conversation) that the decision to vary or not vary the TS depended on the preference of the performer(s) he was writing for, and it made no difference to him. Therefore, should we not create multiple metrical visions/versions of a given Babbitt score to better understand his intent?

Feldman wrote his early non-graphic works without TSs, using a partially spatial, partially insinuative, notation. Then he suddenly began using a very precise, almost conventional notation, with constantly changing TSs. Are we to believe that the early works have no rhythmic "spine", whereas the later works are back to the "I-never-saw-a-downbeat-I-didn't-thwack" school? Are we truly to believe that his intent and intention changed so dramatically?

Cage's early notation used TSs which hardly ever changed, employing a system of cross-beaming to provide enormous flexibility in the rhythmic impetus; he then moved to a type of proportional notation, and ultimately to a "time bracket" notation. Did his underlying ethos change so substantially, and is the notational change a reflection of that change; or is the change in notation just a different prism placed on top of the same obsessions?

The notational Stravinsky of the "Rite" is not that of the "Symphony in C". Does the latter have NO rhythmic discontinuities?

The notational Copland of the "Sextet" in not that of the "Piano Quartet": is this, speaking only rhythmically for now, a different Aaron walking towards us?

Let me not continue to the point of nauseam. Rather I mention an alternative title for this essay: Alia iacta est, The Die Is Cast. I chose this statement by Julius Caesar, made just prior to his crossing the Rubicon, not only as a cheap pun pointing to the chance-like elements involved in any choice of TS, nor as an even cheaper pun regarding hazardous possibilities that may result, but also because, as with Caesar's crossing, there is no turning back once the TS is fixed. Enormous unintended consequences flow from any choice, and no composer is sufficiently omniscient to envisage them all.

The bald truth is, even in this day and age, our TS notation system is not flexible enough to provide clear vision onto all the multiphase rhythmic possibilities a composer may have envisaged. No solution is idiot-proof.

THEREFORE:

Learn how to READ what the music is trying to say, not what the notation imposes; or as Bill Williams said to my father:

"The thing is we need to know is how to read (as Ez would say) in order to GET what the newer way of writing calls for".10

My only dispute with that statement being that it applies equally well to the older way(s) -- indeed all ways -- of notating any text.

And ALWAYS "give blood to ghosts".11

2. Nearly Stationary

The Slow Movement of the Cage 1950 String Quartet in Four Parts

The third movement "Nearly Stationary" is frequently played as though it is nothing but a succession of disjunct events;

but there is nothing about this music - not the fact that it is written by Cage; not the fact that it dates from 1950; not the fact that it is sparse; not the fact that, at the beginning of the piece, the composer indicates a rhythmic structure of 2 1/2 : 1 1/2; 2:3; 6:5; 1/2 : 1 1/2 -- nothing that in any way absolves a performer from the responsibility to function as a member of musical society. None of the above facts exempts the performer from playing with the utmost beauty, and elegance, and precision. None of the above means that one may not connect one event to the next; and certainly none of the above means that the responsibility for creating phrases is removed. Here is the original:

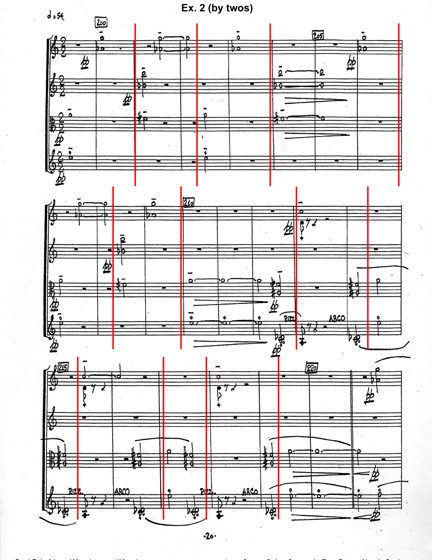

What do I mean when I talk about phrasing this pattern? Consider the first 7 bars. This could be phrased in four groups, the first three being of two events each, the last being the cadence, i.e. ex. (2).

The reasoning behind such a phrasal choice is that the first three phrases will always end on the A-flat-G [major seventh], resolving to measure 204.

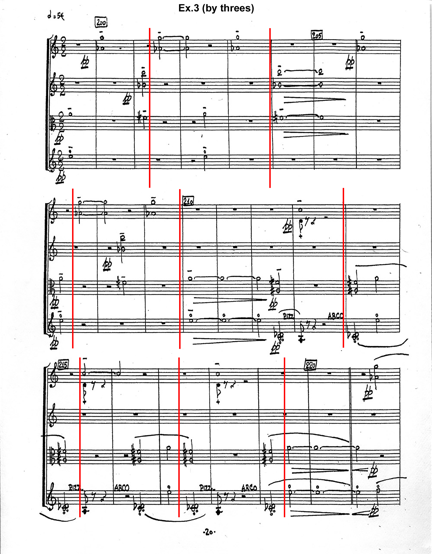

An alternative version would be to have three units, the first two being of three events each, the last group being the cadence.

The reasoning behind that is the permutation of the three rhythmic values (whole note, whole note, half note) followed by the cadence.

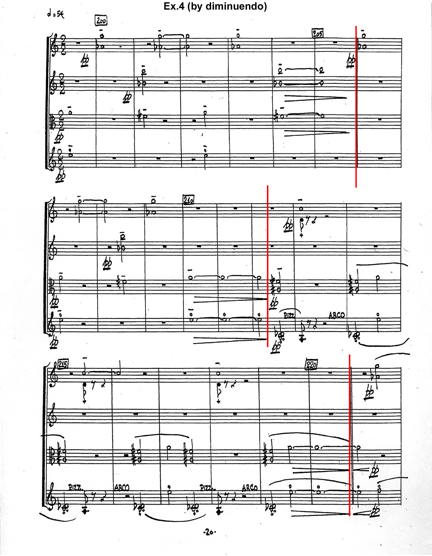

Another possibility is to phrase by dynamic changes:

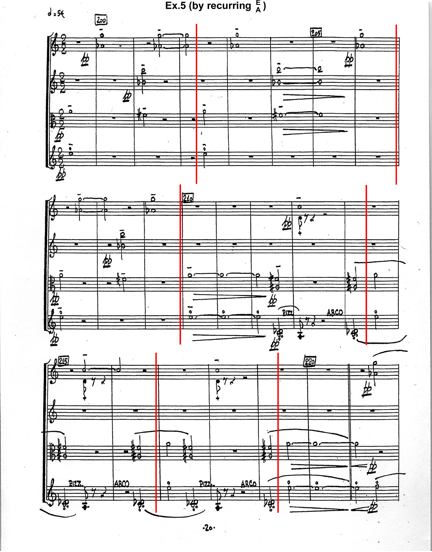

It is also conceivable that one could break these measures into two phrases, the first six phrases being four events, the last being three.

The reasoning behind this version is both the fact that

(a) each phrase begins with the A-E fifth and

(b) phrases are of set durations, i.e. 3 1/2+ 4 1/2 + 3 + 4 1/2 + 2 1/2 + 2 1/2 measures

There are other possible ways of phrasing this, depending on whether you wish to utilize certain aspects of the rhythmic structure, or whether you wish to apply the rhythmic structure on a much broader level than a note-by-note approach permits. But the number of possibilities is not in question here. The point is that there ARE many possibilities, and you are not allowed to NOT think about them just because this is "modern music."

If you were playing a classical work, you would sit and argue about how to phrase; where to breathe; how to bow; what type of stroke; what to emphasize; where to place the tension; where the release; and all of these, and many others, are just as present in these first seven events, as they are in any other music that you care to undertake with seriousness and conviction.

P.S. Be aware that if you do not think, or it does not occur to you to think about such phrasing in a piece such as this, could it be you are not doing so even in classical music?

PRACTICAL SUGGESTION: Given a very slow tempo, one may have difficulty perceiving how to phrase, especially if using only aural cues. That is a fair complaint. The solution is to "SING" (hum, croon, yawl, howl) THRU THE SCORE AT A VERY QUICK PACE, MANY TIMES FASTER THAN THE ORIGINAL TEMPO, in other words, to get a "birds-eye's view" or aerial photograph, so as to be able to conceptualize an impression of the entire scene. Once you have done this, you will find the data has either grouped itself and shown its natural shape, or you can at least have a better feel for how to group the phrases.

3. Earl of Chatham

What Macaulay Can Teach Us About Phrase Lengths

Thomas Babington Macaulay (1800-1859), British author, historian, politician, peer of the realm, is sadly, and unreasonably neglected these days, primarily because his writing style seems far too ornate, not succinct, and is not couched in the two-second sound byte that is today's crummy norm. Among his many writings are Lays of Ancient Rome (1842), History of England from the Accession of James the Second (1848, Vol. 1 and 2; 1855, Vol. 3 and 4; and 1861, Vol. 5) as well as articles from the Edinburgh Review published as a series of Critical and Historical Essays (Longman, 1843), perhaps modeled after Plutarch, which, as with Plutarch, provide enormous insight not only into the person and times being written about, but also into the writer, and his era.

Here are two of my favorite extracts1 from two of the "Essays", hereinafter referred to as "Chatham" and "Pitt".

At this conjuncture Lord Rockingham had the wisdom to discern the value, and secure the aid, of an ally, who, to eloquence surpassing the eloquence of Pitt, and to industry which shamed the industry of Grenville, united an amplitude of comprehension to which neither Pitt nor Grenville could lay claim. A young Irishman had, some time before, come over to push his fortune in London. He had written much for the booksellers; but he was best known by a little treatise, in which the style and reasoning of Bolingbroke were mimicked with exquisite skill, and by a theory, of more ingenuity than soundness, touching the pleasures which we receive from the objects of taste. He had also attained a high reputation as a talker, and was regarded by the men of letters who supped together at the Turk's Head as the only snatch in conversation for Dr. Johnson. He now became private secretary to Lord Rockingham, and was brought into Parliament by his patron's influence. These arrangements, indeed, were not made without some difficulty. The Duke of Newcastle, who was always meddling and chattering, adjured the First Lord of the Treasury to be on his guard against this adventurer, whose real name was O'Bourke, and whom his Grace knew to be a wild Irishman, a Jacobite, a Papist, a concealed Jesuit. Lord Rockingham treated the calumny as it deserved; and the Whig party was strengthened and adorned by the accession of Edmund Burke.

And here is "Pitt":

In our time, the audience of a member of Parliament is the nation. The three or four hundred persons who may be present while a speech is delivered may be pleased or disgusted by the voice and action of the orator; but, in the reports which are read the next day by hundreds of thousands, the difference between the noblest and the meanest figure, between the richest and the shrillest tones, between the most graceful and the most uncouth gesture, altogether vanishes. A hundred years ago, scarcely any report of what passed within the walls of the House of Commons was suffered to get abroad. In those times, therefore, the impression which a speaker might make on the persons who actually heard him was everything. His fame out of doors depended entirely on the report of those who were within the doors. In the Parliaments of that time, therefore, as in the ancient commonwealths, those qualifications which enhance the immediate effect of a speech, were far more important ingredients in the composition of an orator than at present. All those qualifications Pitt possessed in the highest degree. On the stage, he would have been the finest Brutus or Coriolanus ever seen. Those who saw him in his decay,2 when his health was broken, when his mind was untuned, when he had been removed from that stormy assembly of which he thoroughly knew the temper, and over which he possessed unbounded influence, to a small, a torpid, and an unfriendly audience, say that his speaking was then, for the most part, a low, monotonous muttering, audible only to those who sat close to him, that when violently excited, he sometimes raised his voice for a few minutes, but that it sank again into an unintelligible murmur. Such was the Earl of Chatham, but such was not William Pitt. His figure, when he first appeared in Parliament, was strikingly graceful and commanding, his features high and noble, his eye full of fire. His voice, even when it sank to a whisper, was heard to the remotest benches; and when he strained it to its full extent, the sound rose like the swell of the organ of a great Cathedral, shook the house with its peal, and was heard through lobbies and down staircases to the Court of Requests and the precincts of Westminster Hall. He cultivated all these eminent advantages with the most assiduous care. His action is described by a very malignant observer as equal to that of Garrick. His play of countenance was wonderful: he frequently disconcerted a hostile orator by a single glance of indignation or scorn. Every tone, from the impassioned cry to the thrilling aside, was perfectly at his command. It is by no means improbable that the pains which he took to improve his great personal advantages had, in some respects, a prejudicial operation, and tended to nourish in him that passion for theatrical effect which, as we have already remarked, was one of the most conspicuous blemishes in his character.

The first thing to note is that the sentences are of inordinate length relative to present custom. To give an idea of how extensive the sentences are, we provide a table listing, for each sentence, the number of words and syllables, as well as interruptions."Chatham" has 8 sentences; "Pitt" 17 sentences. The shortest sentence (the sixth) in "Chatham" is 9 words. The first sentence (50 words) is the longest. We provide the same information for "Pitt".

CHATHAM

Colons |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

Semicolons |

- |

- |

1 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

1 |

Commas |

6 |

2 |

4 |

1 |

1 |

2 |

1 |

7 |

Syllables |

79 |

21 |

71 |

51 |

29 |

16 |

68 |

34 |

Words |

50 |

15 |

49 |

34 |

17 |

9 |

47 |

22 |

SENTENCE |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

PITT

Colons |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

1 |

- |

- |

Semicolons |

- |

1 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

1 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

Commas |

1 |

5 |

1 |

2 |

- |

4 |

- |

1 |

15 |

1 |

4 |

5 |

- |

- |

- |

2 |

5 |

Syllables |

19 |

100 |

27 |

30 |

24 |

62 |

16 |

21 |

138 |

14 |

34 |

79 |

21 |

24 |

36 |

23 |

76 |

Words |

13 |

69 |

23 |

20 |

17 |

36 |

9 |

14 |

94 |

12 |

23 |

62 |

11 |

15 |

20 |

15 |

52 |

SENTENCE |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

9 |

10 |

11 |

12 |

13 |

14 |

15 |

16 |

17 |

The syllable information is perhaps of less interest, but it is useful to be reminded that changes in the number of words are not necessarily reflected by changes in the number of syllables. Of far greater interest are the number of commas per sentence, and how they are distributed, as that provides a sense of the temporal progression needed when reading.

All this can be associated with music as follows:

Think of the entire paragraph as a movement, or perhaps a subsection of a movement. Think of a sentence as a phrase; and consider the commas to be indications of sub-phrases, or sections delineated within a phrase. For words, think bars. Notice once again how different the sentence/phrase lengths are in terms of the number of words/bars per phrase/sentence. One might say that there are no sentences short enough to represent really short musical phrases e.g. 3-bar phrases; but I assure you, Macaulay knew how to write 3 or 4 word sentences. Far more important, consider the differences between phrase lengths of x bars or words versus y bars or words, and the variability between short and long sentences/phrases. Haydn, Mozart, Beethoven etc show similar structural variability; and just as Macaulay does not parse neatly into identical little packets, H, M & B also do NOT uniformly parse into little piles of 4, 8, 16, and 32 bars, as we have been brainwashed into believing by most of our teachers and colleagues.

There will be those who say that music is not speech, is not writing; that music is related to dance form, and that the analogy to speech, even to poetry, is at best specious. My answers are:

(a) there are many aspects of dance, including Western dance, which are not as four-square as everybody would like to believe;

(b) dance is far from the only influence in Western classical music. One must include: chant (as in Gregorian, or other Plain Chant); epic poetry, which was essentially sung speech; song, such as the troubadours', or even the English madrigalists'; folk music, etc. All these aforementioned have had at least as much influence on music as does dance, and none (with the possible exception of certain poetry) falls easily into equidistant metric structures.

Now speaking of equidistant metric structures, not only do we attempt to parse our metric structures into units of 4, 8, 16, 32, but we also shove in something called a barline, which we do at equidistant intervals.

Now to truly offend EVERYBODY:

What would be the result were we to insert barlines into Macaulay?

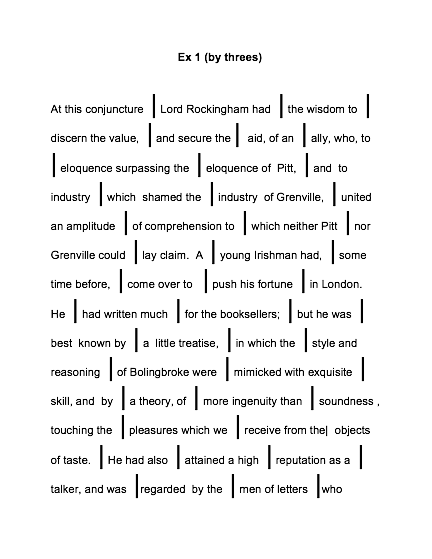

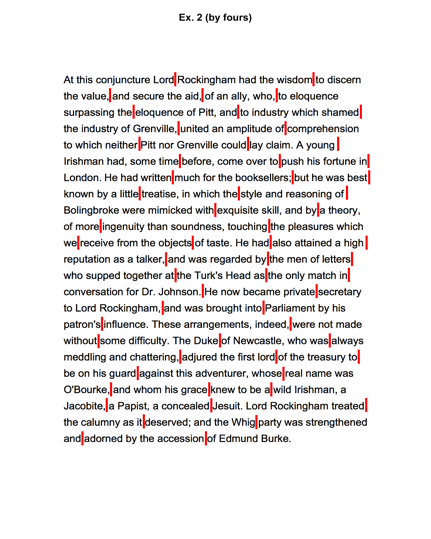

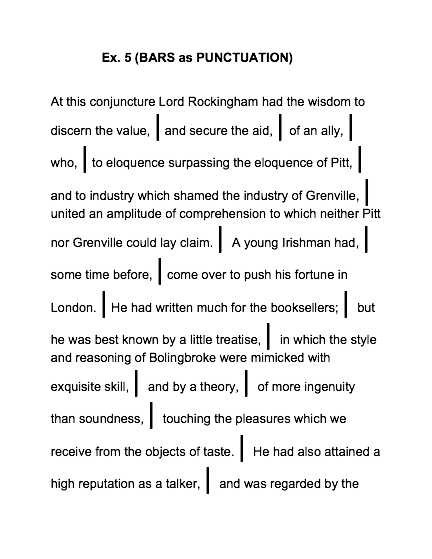

Here are two versions taken from the same example of Chatham, where in one example, we have inserted barlines every 4 words (as in ![]() ); the other of which has barlines every 3 words. Try to read the example faithfully, paying attention to the barline, stressing the first and last words, bringing to the fore the 4-ness or 3-ness of the respective versions. What, if anything, does this add to your understanding or comprehension, to your affinity or enjoyment in reading this? Very well, you will say, this is a completely artificial construct, and I have not taken into account the fact that the words, when read, are spaced apart through the use of commas.

); the other of which has barlines every 3 words. Try to read the example faithfully, paying attention to the barline, stressing the first and last words, bringing to the fore the 4-ness or 3-ness of the respective versions. What, if anything, does this add to your understanding or comprehension, to your affinity or enjoyment in reading this? Very well, you will say, this is a completely artificial construct, and I have not taken into account the fact that the words, when read, are spaced apart through the use of commas.

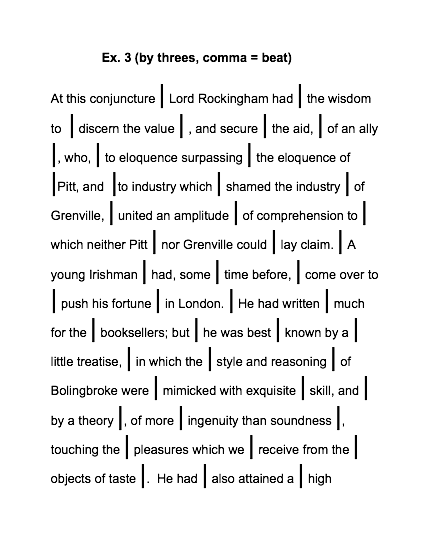

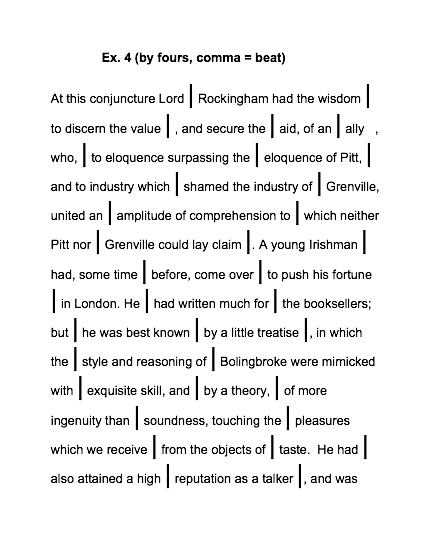

Here are two more versions where we have once again divided things into the equivalent of ![]() or

or ![]() but this time we have made the assumption that a comma or stop is the metric equivalent of a word.

but this time we have made the assumption that a comma or stop is the metric equivalent of a word.

Are these versions "better" or not? In other words, are the barlines less problematic because we have given temporal weight to the commas, etc.? I personally believe that these versions are in fact an improvement, but no thanks to the barline. It is the spacing out of the words which diminishes the power or importance (prominence) of the barline, thereby making it less disruptive, less offensive.

Now you will say, this still is an artificial construct because we all know that no matter how far we spread apart the particles of speech, the entire concept of prose is antithetical to a set of equidistant stresses, but if that is true, why do you want to take music, purportedly the higher art, the more metaphysical, the art not encumbered by the need to convey meaning or fact or data or idea and force that higher art into a series of prison cells?

You may also say that the congruences between Macaulay and music are too great and there is no way that one can utilize barlines so as to satisfy the style of Macaulay's writings.

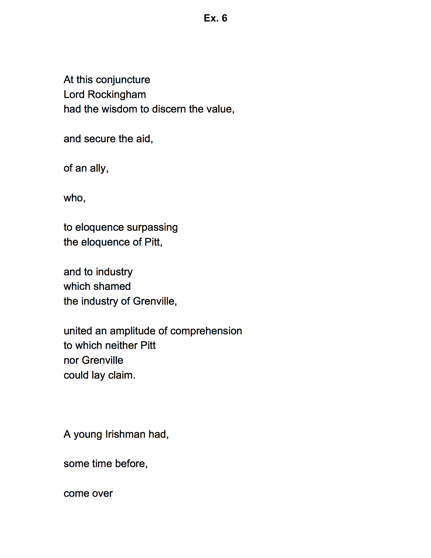

Here is an example where, for commas, we have substituted barlines, and for semi-colons and periods, we have substituted double barlines. I put it to you that these variable-length barlines are not disruptive to what Macaulay is doing.

And last, a version which approaches poetry, with each segment within a comma on its own line. Note how placing the text in this manner leavens it, allows it to "rise".This use of space is not unknown among speakers. Churchill -- in the typescripts of his speeches -- would leave large (vertical) spaces on the page, so that he would know when to pause, the placement of all such dramatic pauses carefully thought out beforehand and used to clarify the meaning, increase the tension, and keep the audience enthralled.

But all this is the art of rhetoric (or as Adam Smith would spell it, rhetorick), defined by the Century Dictionary as:

"that art which consists in a systematic use of the technical means of influencing the minds, imaginations, emotions, and actions of others by the use of language."

But is not what musicians do that very same art of rhetorick, except that we do not have words to help convey meaning (but then neither do we have the misunderstandings and misinterpretations that arise from those same words)?

Therefore, to hell with the barline, and the straightjackets imposed by a stultifing notation, and before you take a musical phrase, and blindly start to perform it believing that all is best disposed within a Cartesian grid of 4x4 squares, remember Macaulay; remember your rhetoric; remember how variable are the number of words per sentence; and remember how variable are the subphrases within those subsentences, and how rarely, if ever, equidistant and invariant thwacks actually give aid and succor to shape and meaning.

What can Macaulay teach us about musical phrasing?

[PZ only sketched how he would answer. He had planned to refer to:

* Material towards the end of Adam Smith's Lectures on Rhetoric and Belles Lettres (ed. J. C. Bryce, Liberty Fund, Indianapolis, 1985), a book that can be read by analogy to music.

* Schubert's Great C Major Symphony, which can be heard by analogy to Macaulay's prose:

"Schubert's phrase lengths are quite astonishing. In some sense, I find them much harder to deal with then H(aydn). I have been dabbling on and off with the great C major, and it is just incomprehensible. I realize it has something to do with counting every two bar phrase as a single unit, but beyond that, I am lost." (PZ email to Anton Vishio, Oct 31, 2014).

* Schoenberg's writing about musical "sentences" in Beethoven (PZ's comment: "ugh"):

In its opening segment a theme must clearly present (in addition to tonality, tempo and metre) its basic motive. The continuation must meet the requirements of comprehensibility. An immediate repetition is the simplest solution, and is characteristic of the sentence structure. If the beginning is a two-measure phrase, the continuation (m. 3 and 4 [Beethoven op2/1]) may be either an unvaried or a transposed repetition. Slight changes in the melody or harmony may be made without obscuring the repetition. (Schoenberg, Fundamentals of Music Composition, ed. Gerald Strang, Faber & Faber, London, 1967)

Compare/contrast Schoenberg's dictat on short-short-long to Adam Smith in Lecture 5:

Let that which affects us most be placed first, that which affects us in the next degree next, and so on to the end.

I will only give one other Rule with regard to the arrangement which is Subordinate indeed to this great one, and it is that your Sentence or Phrase never drag a Tail.

To limit and qualify what you are about to affirm before you give the affirmation has the appearance of accurate and extensive views, but to qualify it afterwards seems a kind of Retractation and it bears the appearance of confusion or of disingenuity. (Smith, "Lectures on Rhetorick")

PZ was also fascinated by Smith's idea that language may evolve from inflected (as in Greek and Latin) to less inflected (as in English):

It is in this manner that language becomes more simple in its rudiments and principles, just in proportion as it grows more complex in its composition, and the same thing has happened in it, which commonly happens with regard to mechanical engines. All machines are generally, when first invented, extremely complex in their principles, and there is often a particular principle of motion for every particular movement which it is intended they should perform. Succeeding improvers observe, that one principle may be so applied as to produce several of those movements; and thus the machine becomes gradually more and more simple, and produces its effects with fewer wheels, and fewer principles of motion. In language, in the same manner, every case of every noun, and every tense of every verb, was originally expressed by a particular distinct word, which served for this purpose and for no other. But succeeding observation discovered, that one set of words was capable of supplying the place of all that infinite number, and that four or five prepositions, and half a dozen auxiliary verbs, were capable of answering the end of all the declensions, and of all the conjugations in the ancient languages.

But this simplification of languages, though it arises, perhaps, from similar causes, has by no means similar effects with the correspondent simplification of machines. The simplification of machines renders them more and more perfect, but this simplification of the rudiments of languages renders them more and more imperfect, and less proper for many of the purposes of language. (Smith, "Considerations Concerning the First Formation of Languages")

Which reminds of Schubert's Great C Major making its long, complex phrases out of simple components.

Beside the content and form of phrases is the issue of how to properly declaim them, e.g. the need for pauses after Macaulay's commas:

Rhetoric is exactly what we are talking about, i.e. performances which only (indeed stupidly) pay attention to the exact written letter are meaningless; probably harmful... (PZ email to Yuji Takahashi on May 7, 2016).

- Craig Pepples, Aug 2017]

4. What if Papa Haydn...

Call me a disestablishmentarian, but I remain,

Disestablishmentarian that I am,

Disestablishmentarian tho I am,

constantly a-Paul-ed by the unidimensional, nay, simple-minded view most musicians have regarding notated meters, and metric usage, in "classical", and other musical periods. Even major composers of the last century, who in their own music admitted the irrelevance of the barline, and/or resented its strictures,

and thought nothing of assuming that previous generations could not possibly think as modern composers do, and hence condemned their forebears to metrical prisons.

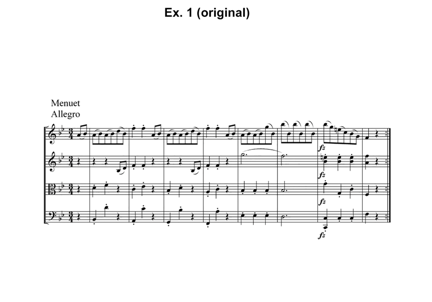

As example, let us vivisect some bars of Haydn's String Quartet op. 76, no.4, IIIrd movement minuet, (hardly a unique example!), the first eight bars of which nominally read:

This is usually performed in a cutesy-poo, affirmatively-innocuous, narcolepsy-inducing state usually referred to as "style", or as Lewis Carroll would have it:

"The style is that which is usually known as 'Early Debased': very early, and remarkably debased."1

with most downbeats being heartily thumped, in case we did not know that minuets are occasionally in ![]() .

.

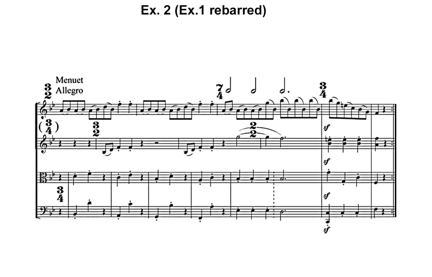

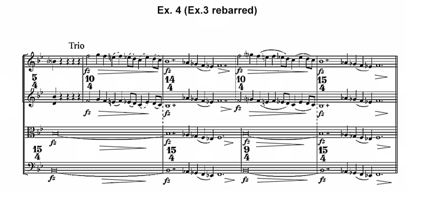

But let us suppose, just suppose, that, rather than the de rigueur ![]() "tub-thump", what good old rascally papa H really had in mind was a portrait of three or four stumblebums who would not know a dance step if it bit them in the nether regions (a fair description of your writer), and who could not determine the downbeat (not a fair description of your writer - I can determine them; I just do not like them); each stumblebum with a different idea as to what the meter, and where the downbeat; each bum utterly convinced of his own correctness until, in a desperate panic, they all (sf) clunk down together at the penultimate moment before catastrophe. In short, suppose Haydn had wanted something that might be better understood had it been notated:

"tub-thump", what good old rascally papa H really had in mind was a portrait of three or four stumblebums who would not know a dance step if it bit them in the nether regions (a fair description of your writer), and who could not determine the downbeat (not a fair description of your writer - I can determine them; I just do not like them); each stumblebum with a different idea as to what the meter, and where the downbeat; each bum utterly convinced of his own correctness until, in a desperate panic, they all (sf) clunk down together at the penultimate moment before catastrophe. In short, suppose Haydn had wanted something that might be better understood had it been notated:

Here the imbecile first violin BOLTS prematurely out of the gate, sawing away in ![]() to his heart's content; the viola and cello blat their

to his heart's content; the viola and cello blat their ![]() "oom-pahs" but NOT in synchrony with the first violin; and the second violin, desperate to join the fray, decides to more or less side with the first violin in terms of

"oom-pahs" but NOT in synchrony with the first violin; and the second violin, desperate to join the fray, decides to more or less side with the first violin in terms of ![]() , but is "out-to-lunch" in terms of coordination, ultimately deciding to hold on to a G♮ while pretending to not be hopelessly lost in this anarchy, which reigns supreme until that moment of:

, but is "out-to-lunch" in terms of coordination, ultimately deciding to hold on to a G♮ while pretending to not be hopelessly lost in this anarchy, which reigns supreme until that moment of:

"OOPS -- WE ARE SUPPOSED TO BE TOGETHER AND IN ![]() AND THE DOWNBEAT IS"

AND THE DOWNBEAT IS"

NOW!!!

which occurs at measure 6, at the notated "sf" -- probably the reason that "sf" is there, i.e. to clarify the locus of convergence.

Now there will be those who will argue that a minuet is a dance, and therefore thunks on the barlines and downbeats are part and parcel of the concept, and stylistically may be of paramount importance.

Disestablishmentarian that I am, I would argue that is specious because:

if you believe this minuet is not an art-minuet, but rather a representation of reality, anyone who has ever seen genuine folk dancing (that is not carefully nurtured and/or cultured for anthropologists, tourists, Las Vegas, etc) will immediately understand that the participants are not always well coordinated; not always graceful and lithe; and often take a while to settle into a physical rhythmic unison2, i.e. Ex. 2 is a closer simulacrum of actuality than is the original notation.

If, on the other hand you wish to argue:

that a Haydn or similar minuet represents the quintessential ennoblement of a simple-minded peasant activity, you are hoist upon your own petard, since version (b) is the far more elevated, experimental -- and some might even say, aristocratically corrupt and decadent -- version.

People might also argue that the "sf" is where it is because H wanted to emphasize the harmony at that particular point; but are we really to believe that the writer of The Seasons etc thought a V7 in the penultimate of the "A" section of a minuet something SO terribly unusual and/or harmonically interesting?

There will be others who will argue that music from this time period never involved conflicting and conflicted meters, or certainly not to such an extant. Why then, did Koch, and various others, bother to define the concept "imbroglio" in a musical dictionary? Even the Century Dictionary manages to define "imbroglio"3 as:

a concept that seems to have vanished from our collective musical consciousness in the latter half of the 20th century.

So on which grounds do you wish to fall on your sword?

In another example from the same movement, notice how the basic notation conspires against us!

What is disguised is how this 17-bar exposition (plus one bar from the earlier 2nd ending, totaling 18) clearly parses into V+V+III+V (in terms of measures).

But what happens if we renotate as:

With the appearance of the "Lungas" in the lower voices, suddenly the voice of the dudelsack is heard throughout the land, and bird droppings keep falling on my head -- a much different scenic image from Stomping-on-Every-Downbeat, At-the-Palace.

Here the "sf" clearly serves to delineate phrase structure, because the harmonic stasis of this example does not allow an alternative explanation centered on harmonic change.

Now I will NOT ask you to believe that any of the above was actually Haydn's intent (although in the interest of full disclosure, you should know that I am firmly convinced it was); BUT, do you really want to argue that papa H was:

not intelligent enough

not mischievous enough

not experimental enough

not observant enough

not alive and aware enough

basically too brain-dead

to have had such a musical thought?

Now I make no claim to any clairvoyance in regards Haydn's mind, and have little faith in people who do so claim...4

but even if you truly believe such an analysis is unrealistic, every now and again it is important to consider that:

"we have here a proposition that could hardly apply to reality under any conceivable circumstances; and which is nevertheless of the utmost importance in order to understand this reality." (Schumpeter, History of Economic Analysis p.1050)

So for those of you who have NOT "arrived at full knowledge of the subject without knowing the facts" (Pound, ABC of Reading, p. 9) and who might like to explore the possibility, I WILL ask you to seriously consider:

How was H supposed to notate the above if this, or some other close approximation, is what H actually had in mind, and wanted us to realize, think and play?

Had Haydn been writing some hundreds of years earlier, there would be no score per se, and each voice could be notated individually, in isolation; but the form was different in Haydn's time. Note that it was the form that changed. That does not mean the idea itself was dead, or that H could not imagine it!

With very, very rare exceptions, convention would not allow H to switch meters within the same movement, and certainly not within a section of a movement. Specifying two simultaneous yet different time signatures was also not allowed; and once again, I must point out that we are speaking of a notational convention -- the fact that it was not allowed to be notated is not evidence that H could not think it.

Haydn could not have easily notated displaced downbeats.

Yes, he could have used beams across barlines, but that would not work for quarter-notes; and there is not much evidence that he extensively used beaming against the barline (again I emphasize: the absence of such cross-beaming is not evidence that he did not, or could not, or would not, think in those terms).

Yes, he could have cluttered the page with "sf"s or "sfz"s, but that would have not been a panacea since:

(a) if multimetric rhythmic thinking WAS the norm, those markings would at best be redundant, and at worst would obfuscate;

(b) if multimetric rhythmic thinking was NOT the norm, the dynamics might have been thought of as they are today i.e. accents against a grid, but not necessarily an indication to displace the grid.

What then was the man supposed to do in order to achieve the result of Ex. 4?

The answer to that question, at least in the Robbins Landon edition of H. (my personal favorite) is to put nothing in the score except for that single "sf", thereby leaving the maximum flexibility (within the bounds of reason) to the performer's judgment. On the other hand, this is not a case where what the law does not expressly forbid, it allows.5

THE MAIN POINT:

"LISTEN to the sound that it makes." (Pound, ABC of Reading, p. 201)

PLAY WHAT IT IS, NOT WHERE IT IS

PLAY HOW IT SOUNDS, NOT HOW IT IS WRITTEN

When thinking about metric stresses in what appears to be a fairly conventional context, keep in mind that the notation can be particularly deceptive.

Paul Zukofsky

Hong Kong

Aug., 2016

5. MBB

Milton Byron Babbitt (so named after his father's two favorite English poets) provides our example of the "trap of the purportedly complex".

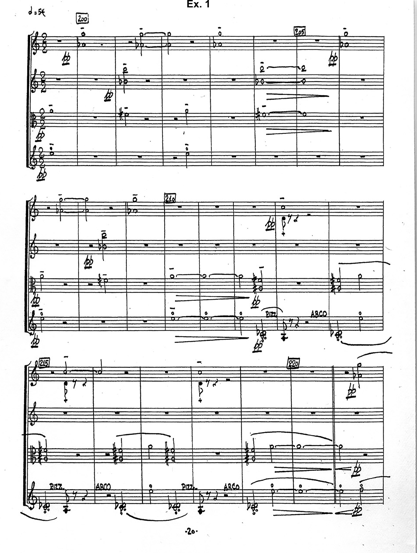

Ex. 1 shows the first 13 bars of his 1993 "String Quartet VI". We "see" a score of filigree and some complexity. As often in Babbitt's music, the initial impression is that it is somewhat hard to figure just where to "hang one's hat".

The work begins with an initial "flurry" which has all the trappings of an "upbeat", including a highly specified quantized crescendo (from the beginning to the final eighth note of bar 1); which eighth note is clearly an arrival point, replete with an "f" (forte), i.e. a type of "downbeat". No amount of blather can change the "persona" of that first "flurry"; certainly not the matter of how the "flurry" is placed relative to some arbitrary barline.

So from the very start, a contradiction appears between how the music "sings" (or at least yowls), vs. where it sits vis-a-vis the sclerotic barlines.

Why would that be? Quartets there are that, unfortunately, try to eviscerate themselves on the downbeats, while further contorting themselves to play what they believe are upbeats; but Babbitt's use of a constant time signature (in this, and other works) is a choice made at the preference (and presumably convenience) of the group being written for. He could have cared less (in his own music) about a downbeat vs. upbeat metrical dichotomy;1 and had such "gestures" interested him for his own music, he certainly knew enough examples to draw upon. Yes, his music has "procession"; but not dictated by musical gesture, or nominal time signatures.

More importantly, barlines in Babbitt rapidly become nugatory, given his concerns with portraying similar "musics" at different speeds; for the notation of music at simultaneously different speeds; in a manner that reveals and/or preserves the real shape of the music; and doing so within the confines of single time signatures; is essentially impossible. 2

So if, by Babbitt's own admission, the barline is more or less sym-sham-bolic, often either irrelephant to the flow of the music, or a direct hindrance, what can players use to better orient themselves in time?

Ex. 2 presents guidelines or guideposts showing one approach. Red verticals show where all four members of the quartet have a simultaneous attack (aka a simultaneity); i.e. players MUST be together at those places! These simultaneities are then used to establish a series of time signatures (in red) that may better "group" things than do the nominal time signatures provided. Red verticals are not to be construed necessarily as having structural significance (as discussed in traditional analyses of Babbitt's music), although they may in fact have such significance. For our purposes, red verticals are simply those places where the performers must be together, and can regroup with safety, and relative ease.

That being said: points of simultaneity are, or can be, places where manifold thoughts, speeds, units. etc. meet. Points of Simultaneity [PoSs] can also be where ideas, phrases, gestures, etc. end, and then begin anew. PoSs are, also by definition, different - i.e. in the most simplistic, perhaps even simple-minded, sense, PoSs are the moments when the individual player cedes independence in favor of the group; in opposition to those areas where things need NOT be quite so vertically "tight", and the claims of the individual trajectory become outstanding. If your perceivers, aka your audience, cannot tell the difference between which of these polar opposites is paramount at any given time, you have lost track of the most basic tenet of rhythmic organization.

Comparing Ex.s 1 vs 2, we find that Ex. 1 shows three ![]() measures; plus a fourth

measures; plus a fourth ![]() with an additional 16th note; followed by seven

with an additional 16th note; followed by seven ![]() bars, etc. whereas Ex. 2 shows a

bars, etc. whereas Ex. 2 shows a ![]() followed by a

followed by a ![]() ; then a

; then a ![]() ; then a

; then a ![]() , and then a

, and then a ![]() . In other words, Ex.2 starts to provide some sense of phrasing, and pacing, which one should know BEFORE one attacks any work (see "Nearly Stationary" in this collection). Dutifully only counting beats in bars will eventually "get you thru the composition", but without much understanding, or anything else.

. In other words, Ex.2 starts to provide some sense of phrasing, and pacing, which one should know BEFORE one attacks any work (see "Nearly Stationary" in this collection). Dutifully only counting beats in bars will eventually "get you thru the composition", but without much understanding, or anything else.

Bottom line: if the red verticals (and the blues we will meet in Ex. 3) connect actual simultaneities, whereas the barlines may or may not, to what should we be paying attention? An unheard, impossible to convey (certainly not without distorting the "real" phrases) barline? Or those places where we MUST be together?

Continuing in the steps of Ex. 2, Ex. 3 provides subsidiary "blue verticals" connecting (usually) two simultaneities. These connections show relationships different from that of the reds; and we now need to decide how to differentiate these internals within the larger "red" phrases. For an example of how this might work, consider the first four notes in viola (va.) in our ![]() measure.

measure.

There used to be a wonderful New York City Parking Regulations sign that lived on Fifth Av., close to the S.W. corner of 57th St.; which read:

DO NOT EVEN THINK ABOUT PARKING HERE.

I once asked a cop if people parked there anyway. The answer was "of course". As with that sign, the following caveat too will not be paid attention to. Nevertheless:

DO NOT EVEN THINK ABOUT

syncopating these four va. notes. They are NOT syncopations.

The notes (of vln. II) are simply three values (two dotted 16ths, followed by a dotted eighth) in the nominal (not actual) relationship of 1:1:2; and the va. presents four "equal" valued dotted 16ths i.e. 1:1:1:1. Given an indicated tempo of Quarter Note = MM = 84 (approx. 714 msec per Quarter Note); any dotted 16th = MM = 224 (msec. = approx. 268); and a dotted eighth = MM = 112 (msec. = approx. 536).

Now we ask: what exactly must we do so that the four "equal valued" dotted 16ths convey their "fourness" i.e: do you consider these four to be a "choriamb"? 3 i.e. an initially prolonged first note; followed by two briefer notes, terminating in a final elongation of the 4th note; or are these four notes just pairs of "trochees" (i.e. long/short real values); or rather "iambs"? (i.e. short/longs)? For all three choices ("choriamb"; "trochees"; "iambs") one may expect changes in the msec. values of the dotted 16th in the area of +/- 10 to 20+ msec.4

All this the performer must judge and evaluate, so as to let each voice speak what it must say!

Vln. II then presents another set of three values in the relationship of 1:1:1 (written as three 16ths of MM. = 336 (msec. = approx. 179); leaving "open" (at a minimum) the implications:

Is this a reference to the 1:1:2 previously presented, but sped up (note the similarity in pitch content shape)?

Is it a reference to the four equidistant va. values of the first beat (vln. II does carry over for a fourth note on the next nominal downbeat), also sped up?

Or something else entirely? i.e. a leading in to the group of "nine" triplet 16ths (even quicker still at MM. = 756 per; msec. approx 79)- that introduces the 3rd red vertical, and a somewhat different "quality" in the music?

And all of the above groupings must be shaped so as to be recognizable as groups of notes, and should not be heard as being placed against a grid - i.e. play WHAT it is; NOT where it is.

One could continue in this vein but ----

Some people will say that to think shapes will result in rhythms that are not "precise".

"Precise" measured against WHAT? What is your ruler? The grid (i.e. bar-line, or nominal quarter-note, or division thereof) vs. "shapes" at different speeds are antithetical. I.e. if you wish to convey groups of notes, at different speeds, each with their own shapes or contours (such as a group of 3 or 4 notes of nominal identical values), you can not do so to the msec. if your standard of precision is that of the grid.

So what to do?

Fit everything to a meaningless quantized simulacrum of false reality, claiming (spurious) "accuracy"? Or rather let each voice say what it must, but without going so far astray as to utterly destroy all vertical rhythmic relations?5

Remember that these four members of the quartet do NOT always march to the same drummer. Some times there needs be 4 drummers; some times fewer; some times the voices combine to form composite rhythms that have significance; some times the voices are synchronous; even simultaneous; some times in conflict; and to assume that one grid fits all (other than in the wholly artificial world of data plotting) is to not understand or appreciate the underlying "conversation" or "gestalt". Yes, it is imperative that simultaneities are (within human capabilities) simultaneous; but other than that, each voice must breathe its own cadences; its own rhetoric; its own syntax.

Also remember, musics occurring at multiple speeds is hardly a new concept i.e. think of Otto Luening's joyous reference to the three great "Irish" composers:

O'Ckeghem; O'Brecht; and O'Dufay;

(as well as many others not Irish)!

Finally, and to not (yet again) invoke the Stravinsky vs. Busoni Scylla and Charybdis6; the problem we have been discussing is not only not new. It is a problem NOT exclusive to music.

When St. Jerome was first translating the "word of God" in to what became the "Vulgate", he ran in to a very similar problem i.e. the literal word of the Bible was considered sacred; and because of that, there were those who argued that one must ONLY do a word-for-word literal translation, as anything else would be sacrilege. But a word-for-word translation of anything can be quite, quite dull; often makes little to no sense in the new language; and sometimes conveys a meaning opposite to that of the original. Jerome's solution was a freer translation which raised meaning, or intended meaning, over the literal word; and for doing this, Jerome received more than his fair share of venom. For the record, I agree with Jerome; and for those who are not really certain what Jerome has to do with Milton Babbitt, for the literal "word of God", substitute the composer's final written version of the composition;7 and for "meaning", substitute a method of reading what the rhythm is supposed to be, vs. where it is.

Therefore, do not be blindly, and rather stupidly, faithful to the exact rhythmic notation. Rather, "convey" the underlying thought, and think phrases, "shapes", no matter how the scholars scoff. Without having something to say, and a way to make/speak/shape what you wish to say, no numerology will save you.

Let us now briefly compare aspects of the musical content of the Babbitt and the Haydn from the previous article in this collection; and here is where life becomes amusing again.

Renotation of a Haydn "Trio" can completely change what we sense, smell and/or feel from the music. But is such renotation any more fundamental than Babbitt's disregard of the traditional meaning of time signatures? Or is it the same game played in reverse? And thought about in those terms, are the problems of the Babbitt really all that different from the imbroglio of the Haydn?

The salient question: is this rewriting, this rethinking of Babbitt, truly that different from what we did with the Haydn?

Even in this day and age our notation system is still not flexible enough to provide clear multiphasic rhythmic presentation. But not to have our argument too circular, if Babbitt, and Carter, and Messiaen etc. cannot find a flexible and clear enough notation, what chance did Haydn have to get the point across, given the limitations and restrictions of rhythmic notation of his time?

Paul Zukofsky

Hong Kong,

Sept., 2016

6. Who Wrote This?

For a (particularly a-cute) case of the refusal to ask "what if", consider the rhythmic neume in Ex 1.

Think durations only (measured from "attack" to "attack").

Nothing else.

Who might have utilized, or desired, such an Ex.1?

Compare Ex. 2 with Ex.1.

What are the differences?

Ex. 2 has a time signature, and starts with a quarter note rest. Thereafter:

Ex. 1 first shows a dotted quarter note worth six 16th-notes. Ex. 2 also shows a dotted quarter note (but written as a quarter-note tied to an eighth- note).

After the dotted quarter note, Ex. 1 shows a quarter note. So does Ex. 2.

Ex. 1 then shows a quarter note followed by a + (meaning five 16th notes). Ex. 2 notates this with an eighth-note, tied to a dotted eighth note; and so on.

In short, the examples are nominally arithmetically identical, the difference being the use (in Ex. 2) of a time signature, and barlines; vs. an unencumbered, durations-only, style. Both examples are the opening bars of Wagner's "Vorspiel" to "Parsifal" (Ex.1 is NOT a quote from Messiaen!).

How should one think about, play, these examples?

"Musicians" there are who hold that one should indicate the beats, or at least the downbeats, of Ex. 2; as opposed to having no such davens in Ex. 1.

How is one supposed to indicate the beats of Ex. 2?

With genteel swells, constipated grimaces, or little vomitings?

None of these exist in the original score; and as Wagner was capable of at least notating small cresc/dim, why assume that Wagner wanted such swells, grimaces, or vomits?

Would the vomits help or hinder the impression of time illimitable, so fundamental to "Parsifal" (and for that matter to Cage's "Nearly Stationary")?

Music exists in sound. How that sound is coded on paper is an interesting exercise, perhaps a clue as a means towards an aural end; but the coding is not the same as the solution.

What utility do Wagner's meters serve (other than keeping a large group of players more or less together)?

What function can the meters serve, especially when they cannot, indeed should not, be heard?

Ex. 3 shows the full score.

For the first 5 bars all is unison. No grid or marker(s) allow one to aurally measure how the opening "chant" might be plotted.

All is inchoate; rhythmically "without form, and void" ("...And the Spirit of God moved upon the face of the waters")1.

And the first real "arrival point" of the work (the A flat major chord in the middle of meas. 6) does NOT occur on a downbeat!

So how does one indicate, let alone convey, "beats"?

If one must, one can think of them internally; but what one thinks, and what is heard, are not the same!

Speaking of downbeats:

how many "pitch-classes" (of these first measures) actually occur on a downbeat?

Only two!! G natural on downbeat bar 3 (cleaving the opening phrase into 7 + 12 quarter notes); and the final "landing" C natural (bar 6). Other than for these, there are no downbeats!

Beyond the above two "pitch-classes" that occur on a downbeat, how many occur on any whole beat?

Five!

First A-flat bar one, beat two.

F natural, bar 2, beat 2.

C natural, bar 3, beat 2.

E flat, bar 3, beat 3.

D flat, bar 4, beat 4.

So obeisance is required to a series of artificial "mileposts" that exist solely in imaginary Cartesian space; "mileposts" imposed upon a simulacrum of plainchant (which is a thing without rigid bar-lines, or even precisely defined individual note-values)?

In what rational (even irrational) world does that make any sense?

And then there is the high probability that Ex. 1 is almost certainly far closer to Wagner's "intent" than is Ex. 2.

Once again, a composer was trapped between the accepted notational possibilities of the time2 and an exploration, and chose the former; but that is no excuse for us to not see the future peeking through "the face of the waters".

Paul Zukofsky

Hong Kong

Oct., 2016

7. Emerson

Our age is retrospective. It builds the sepulchres of the fathers. It writes biographies, histories, and criticism. The foregoing generations beheld God and nature face to face; we, through their eyes. Why should not we also enjoy an original relation to the universe? Why should not we have a poetry and philosophy of insight and not of tradition, and a religion by revelation to us, and not the history of theirs? Embosomed for a season in nature, whose floods of life stream around and through us, and invite us by the powers they supply, to action proportioned to nature, why should we grope among the dry bones of the past, or put the living generation into masquerade out of its faded wardrobe? The sun shines to-day also. There is more wool and flax in the fields. There are new lands, new men, new thoughts. Let us demand our own works and laws and worship.

-- Ralph Waldo Emerson, introduction to Nature (1836)